Complete and utter rejection. That’s what a record number of Republican Party voters in Georgia said Tuesday about former President Donald Trump. Gov. Brian Kemp, whom he blamed for not contesting his narrow loss in the state in 2020, was renominated with 74% of the vote.

The man he talked into entering the race on the only 2020 reconsideration issue, former Sen. David Perdue, won only 22%. Kemp not only won well over the 50% needed to avoid a runoff, but he won over 50% in 158 of Georgia’s 159 counties.

Moreover, Secretary of State Ben Raffensperger, whom Trump blamed even more than Kemp, was renominated, winning 52% of the vote. His Trump-backed opponent, Rep. Jody Hice, had only a handful of tiny counties outside her aged congressional district.

Last week, based on the results of the previous primaries, I wrote that it was “not quite Trump’s party” anymore. This week’s results underline this. Republican primary voters are not Trump’s chess pieces, and Trump is nothing like a chess grandmaster.

The Republican Party, in the state where this issue has been raised most loudly, is the party ready to move forward after the 2020 election. It’s a party that loves leaders who stand up to the mostly liberal media, but wants them to also be effective decision-makers, like Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis or Arkansas Sen. Tom Cotton or former Vice President Mike Pence.

This is a party that has also performed better than usual for an opposition party in the past year. Turnout in primary elections is a good indicator of partisan enthusiasm. Less in states where the party is registered, but even there Republicans performed well, winning 53% in two-party primaries last week in Pennsylvania and 55% in North Carolina, although Democrats have a 7-point registration advantage in Pennsylvania and a 4-point advantage in registration. point advantage in North Carolina.

In states where voters can vote in either party’s primary, turnout among two-party Republicans was much higher – 67% in Texas on March 17, 65% in Ohio last week, 62% in Georgia and 79% in Alabama and Arkansas this week . Only in Oregon did Democrats outvote Republicans, but by a smaller margin (55-45) than in the 2020 election (56-40).

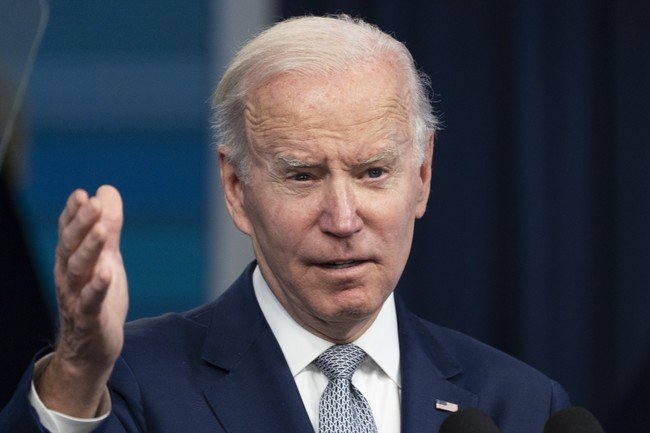

Georgia’s results do not bode well for Democratic gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams, who baselessly claimed to have won the 2018 election, and as to the allegations – accepted and taken as gospel by national Democrats and by Delta Air Lines, Coca-Cola and Major League Baseball Corporate Executives – Republican voting law changes in this state amounted to voter suppression. “Jim Crow on steroids” – in the words of President Joe Biden.

However, voter turnout was high. Republican turnout nearly doubled, 92%, compared to 2018, while Democratic turnout increased 28%. This is not what Jim Crow looked like in the pre-1965 Deep South Voting Rights Act.

Rather, it is an example of an ailment common among higher education advocates of both parties. This is what I call turning Thorstein Veblen upside down, politics as entertainment for theoretical pursuits. It is the cultivation of old-fashioned, historic grievances and the preaching of unattainable goals.

So we have the Democratic candidate for governor of Georgia campaigning against “voter suppression,” which hasn’t been a significant factor in over 50 years. In 1972, Georgia’s white-majority congressional district elected black minister Andrew Young to Congress.

And you have Democrats like Pennsylvania attorney general nominee Josh Shapiro campaigning heavily on abortion. This is not a completely theoretical matter. A Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade, according to Justice Samuel Alito’s draft opinion, would mean Republicans in some states could ban abortion or, more likely, impose restrictions similar to those in much of Europe.

But the practical effect would be constrained. I estimate that most abortions would still be allowed in states where, according to the pro-abortion Guttmacher Institute, 75% to 80% of current abortions are performed.

As for Republicans, the theory pushed by Trump and some supporters is that the 2020 election result could somehow be reversed. But the membership of this theoretical class appears to be shrinking as voters focus on issues – inflation, immigration, crime – where policy can make a difference.

Michael Barone is a senior political analyst at the Washington Examiner, a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, and longtime co-author of The Almanac of American Politics.