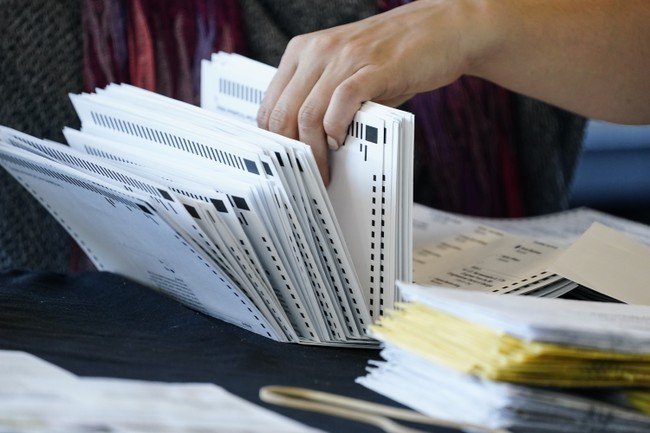

To say the 2020 election was unlike any other in American politics is an understatement. The pandemic interrupted the regular season. Political conventions have ceased to be party celebrations and have become socially distant virtual events. The massive expansion of mail-in voting made Election Day look more like Election Month. And, tragically, the capital riots will be remembered by future generations as a obscure day in our nation’s history.

Longtime Republican strongholds Arizona and Georgia decided to send Joe Biden to the White House. Three historically blue states that delivered the presidency to Donald Trump in 2016 – Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin – returned to the Democratic column last year.

After supporting Barack Obama in his campaigns, Ohio and Florida voted Republican in the last two presidential cycles. Same thing in Iowa.

Virginia and Colorado went from red states in 2004 to competitive purple states in 2008 until Biden’s early call on election night. Missouri, deposed as a leader twenty years ago, has voted Republican every four years since 2000.

Since 1996, twenty states have swing between Republicans and Democrats. Two other states, Nebraska and Maine, awarded electoral votes to both major party candidates that same year.

The only constant change in the electoral college system — and the popular red and blue state map that depicts it — has been change. Yet analysts and editorials apply the red state versus blue state dichotomy to illustrate fundamental differences in state-level governance. In this context, liberal blue states are characterized by high taxes, dominated by trade unions and suffering from an exodus of talent and wealth. Conservative red states are said to be the beneficiaries of blue states voting with their feet, demanding a warmer climate, lower taxes and better business conditions.

There is evidence to support these generalizations. Millionaires are fleeing New York and New Jersey for Florida. California tech companies have moved their headquarters to Texas. However, this elementary sorting and broad categorization based on state presidential preferences, while useful, is imperfect.

West Virginia, which Trump won by 40 points in November, ranks sixth among states in government spending per capita, ahead of Vermont (8th) and Rhode Island (9th). Arkansas, reliably red since Bill Clinton left office, ranks 10thvol in spending, ahead of New York (11th) and Massachusetts (12th).

West Virginia is losing population at a faster rate than Connecticut or New Jersey. Arkansas fell below the 50-state median population growth from 2008 to 2018.

Louisiana ranks 14th, according to WalletHubvol in the overall tax burden. Mississippi ranks 17thvol. Both have higher tax burdens than Oregon and Michigan. South Carolina’s top marginal income tax rate exceeds Massachusetts’ top rate.

Red states like Florida, Tennessee and Texas are booming, fueled in part by a lack of state income taxes and responsible balance sheets. On the other hand, Kentucky, which has voted for Republican presidential candidates since 2000, has one of the most underfunded public pension systems in the country. The ratings agencies put Kentucky in the same company as Illinois – and everyone knows what a fiscal disaster Illinois is.

Whether voters prefer Republicans in presidential elections is irrelevant if a state’s overall tax burden discourages diminutive business start-up or the state’s massive debt signals a lack of seriousness in managing fiscal policy. Entrepreneurs and Fortune 500s alike have too many opportunities to waste time and capital in places where they don’t work together.

Red states can also be blue. It is critical for policymakers to understand where their state stands in order to determine what steps should be taken to compete with states leading the pack.

Andrew McNeill is a former Kentucky deputy budget director and guest policy fellow at the Bluegrass Institute for Public Policy Solutions.