If the presidential nominating process is the weakest part of our political system – and that may not be the case to which the framers failed to allude to it – the vice presidential selection process is definitely a close second. Some might even argue that it is a candidate for the top spot.

This was especially the case in the last two election cycles. The 2016 election, in which the Republican and Democratic candidates were 70 and 69 years ancient on Election Day, respectively, raised the actuarial odds of the vice president becoming president to the highest level ever.

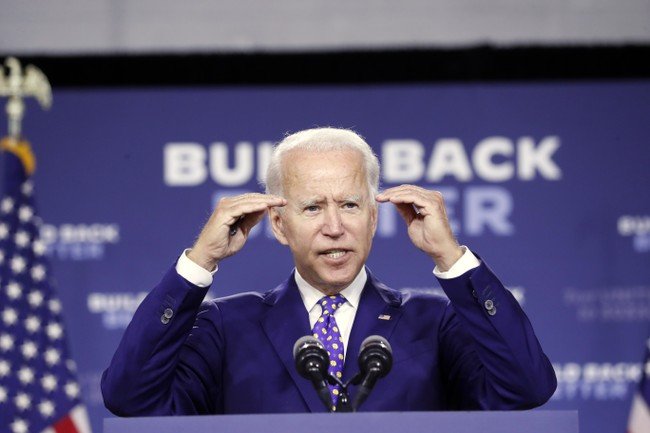

This year, the Republican and Democratic candidates will turn 74 and 78, and the actuarial odds are correspondingly lower. With Vice President Mike Pence certain to be renominated, attention turns to Joe Biden’s election, delayed from the promised “first week of August.”

Foreigners must find it strange that 30 to 34 million people participate in the election of presidential candidates, but it is taken for granted that vice presidential candidates are chosen by only one person. They may also find it odd that Biden constrained his choices to women and apparently – he’s not entirely limpid on this – to women who are now called women of color. This limits the likely picks to a very diminutive percentage, and each of those listed appears to have at least one plausible disqualifying feature.

For example, former National Security Advisor Susan Rice, who had more experience in foreign policy and national security than the others mentioned, was designated a liar by the Obama administration and participated in five Sunday programs as UN ambassador in 2012 to spread the legend of Benghazi. Many Democrats consider Sen. Kamala Harris to be too prosecutorial during her time as San Francisco’s district attorney. Rep. Karen Bass was a large fan of Fidel Castro (Florida has 29 electoral votes). Rep. Val Demings was a cop.

Looking back, the two women previously nominated for vice president, former Republican Geraldine Ferraro and former Gov. Sarah Palin, also had little credentials and glaring weaknesses. However, in my opinion, both performed better in their fall campaigns than the men who selected them had a right to expect. Perhaps Biden’s election will be the same.

There is historical precedent for nominees to choose from a clearly narrow field. From its beginnings, the Democratic Party was a coalition of foreign groups, united and capable of winning a majority.

However, keeping them together can be challenging work. Narrowing the list of vice presidents to women or black women rewards core constituencies of two decades, feminist college graduates and black people. The prospect of a black vice president, especially one with a decent actuarial chance of becoming president, could maximize turnout among black and female students.

Of course, Americans have already elected a black president and almost elected a woman. The prospect of a black woman becoming vice president may seem like no large deal. After John F. Kennedy won the presidency with 78% of the Catholic vote in 1960, Catholic vice presidential candidates were chosen by Republicans in 1964 and by Democrats in 1968 and 1972. All three seats were lost.

Democrats have had to choose from narrow areas of VP opportunity before. In the sixty years after the Civil War, when the party’s core constituencies were white Southerners and Catholic immigrants, it was considered unthinkable to put a Southerner or Catholic on the ticket.

During these years, Democrats – and Republicans – in tiny elections typically nominated northern Protestants from New York, Ohio and Indiana, three immense marginal states. They hoped that a local appeal by the vice presidential candidate could sway enough electoral votes to influence the outcome of the election. We lack polling evidence to show whether this was the case.

However, between 1868 and 1920, every winning ticket and most losing tickets had at least one candidate from these three states, which were the seats of the winning vice presidents in 10 of the 14 elections.

There is a stronger case for balancing seats, at least since former President Jimmy Carter and former Vice President Walter Mondale reinvented the vice president as a working part of the executive branch. All but one of the then-elected vice presidents had a career path and set of experiences that were significantly different from those of the president they elected.

Former vice presidents Walter Mondale, Dan Quayle, Al Gore, Joe Biden and Mike Pence have between 12 and 36 years of experience in Congress, compared with zero to four years for the presidential candidates who elected them. George H. W. Bush and Dick Cheney had decades of experience in foreign policy and national security policy, while the nominees who chose them had virtually none.

Joe Biden, with his expansive experience (36 years in the Senate, 8 years in the White House), is said to be wary of an ambitious vice president and may be tempted to choose someone with little or no experience. Rebalancing the fortunes in this way would not be unprecedented, but it could unnerve voters with a sense of actuarial odds.

Michael Barone is a senior political analyst at the Washington Examiner, a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, and longtime co-author of The Almanac of American Politics.