One of the puzzles in this year’s surprising and unpredictable (including by me) off-year election results is why the Republican victory in the popular vote in the House of Representatives, 51% to 47%, did not produce a majority larger than the apparent 221-214 result. (All numbers here are subject to revision according to final results.)

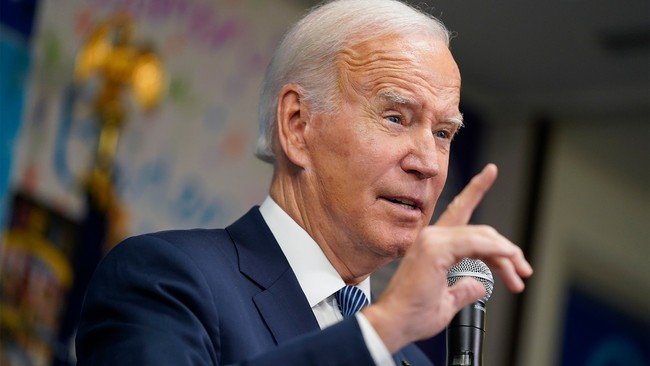

This 51% to 47% margin is identical to Joe Biden’s and Barack Obama’s popular vote margins in 2020 and 2012, respectively. That’s just one digit shy of George W. Bush’s 51% to 48% victory in 2004. That’s almost identical to Democrats’ House popular vote margin of 51% to 48% in 2020, which gave them a nearly identical majority 222 to 213.

The gigantic contrast is with 2012, when Democrats moved the popular vote majority in the House from 49% to 48% but won only 201 seats to Republicans’ 234. How could a party win a 33-seat majority after losing the popular vote, and then only win a seven-seat majority while having a 4-point lead in the popular vote?

One answer is differential attendance. In 2012, Democrats’ electoral advantage was largely due to the vast turnout of Black voters in the election of the first Black president. However, many of these votes were in predominantly Black districts and did not support elect Democrats elsewhere.

This year, mixed turnout worked against Democrats. Turnout in central cities was significantly lower compared to the last off-year election in 2018, down 19% in New York but up 0.3% in the suburbs and upstate; down 13% in Philadelphia but up 8% in the rest of Pennsylvania; down 15% in Wayne County, Detroit, but up 6% across the rest of Michigan; down 12% in Milwaukee County but up 1% across the rest of Wisconsin; down 24% in Chicago’s Cook County, down only 8% in collar counties and downstate Chicago.

This reflects population loss in central cities, especially with black voters leaving the industrial Midwest for the more economically energetic and culturally cordial metro Atlanta – making Georgia, with the third-highest percentage of blacks in the country, a destination state. It also reflects enthusiasm among a largely Democratic electorate after four years of soaring crime and tight lockdowns. This is not a favorable sign for Democratic turnout in 2024.

The second reason is that Republicans failed to achieve a significant enhance in the number of seats in the House of Representatives as a result of the significant enhance in the popular vote resulting from redistricting. Republicans had a vast advantage in partisan redistricting after the 2010 census, but only a minimal advantage after the 2020 census.

In particular, Democratic mapmakers and supposedly nonpartisan but liberal redistricting commissions no longer feel obligated by the Voting Rights Act to place blacks in majority-black districts – a tactic that Republicans have encouraged since the 1990 election cycle because it leaves fewer Democratic voters from neighboring districts.

The abandonment of this supposedly immutable principle, for example, resulted in Michigan not electing a single Black Democratic congressman for the first time since 1952. (A black Republican was elected in mostly white, suburban Macomb County). Democrats also won the state Senate. majority for the first time since 1983, winning districts that combined Detroit’s mostly black neighborhoods with affluent, mostly white suburbs.

The most significant reason why Republicans reduced the number of seats in the House of Representatives was to limit the formation of clusters. Previously, most Democratic voters – black, Latino and aristocratic liberals – were geographically concentrated in central cities, nice suburbs and college towns, while Republican voters were spread more evenly throughout the rest of the country.

The clustering effect can be seen in the number of House districts held by different presidents. Both Bush and Obama were re-elected with 51% of the popular vote. This enabled Bush to capture 255 of 435 House districts in 2004. But Obama had only 209 in 2012. Biden, from 51% in 2020, raised that number to 226.

In recent years, democratic clusters have weakened. One reason is that Democratic groups have become less Democratic. Latinos voted 29% Republican in 2012, but 39% Republican in 2022. The percentage of Asian Republicans increased from 25% to about 40%, and the percentage of Black Republicans increased from 6% to 13%.

Meanwhile, Republican concentration has grown in the wide-open spaces between Appalachia and the Rocky Mountains, from the outlying suburbs and in Walmart and Dollar General further afield.

You can see evidence of which party won seats by majority vote. In 2012, 71 Democrats were elected to the House of Representatives and only 32 Republicans who won at least 70% of the vote. Twenty-eight Democrats got 80% or more, while only three Republicans got it.

According to my preliminary calculations, more than 70 percent of districts approached parity this year – 58 Democrats and 39 Republicans. Only 18 Democrats and five Republicans won with 80% or more.

So 51% of the total Republican votes in the House resulted in a disappointing number of House seats.

But it also signaled residual Republican strength. Republican House candidates had difficulty displacing Democrats in marginal districts. Yet relatively few people have been charged with loudly supporting Donald Trump’s retroactive insistence that the 2020 presidential election was stolen; the few who identified with this view lagged significantly behind the many who disagreed.

Instead, Republican House candidates outperformed their party’s Senate candidates in states including Pennsylvania, Ohio, Wisconsin, Georgia, Arizona and Nevada. They also ran strongly with landslide winners Ron DeSantis and Marco Rubio in Florida.

Republican House candidates won 58% of the popular vote in the South and 53% in the Midwest, two regions that combined for 298 of the 538 electoral votes. Replicating that support is one way an untroubled Republican candidate can win 270 electoral votes in 2024.